Date: about 1770

Maker: Cabinetwork by Jean-Henri Riesener; model designed by Jean-François Oeben

Materials: Oak, purplewood, tulipwood, mahogany, stained woods, ebony or ebonised wood, box, gilt bronze

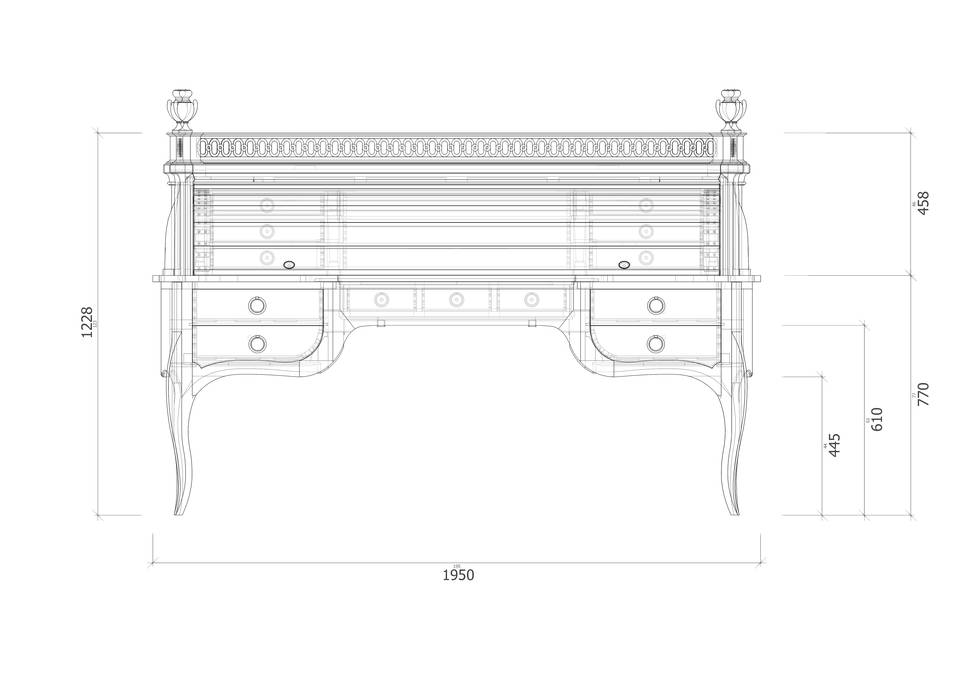

Measurements: 139 x 195.5 x 102.5 cm

Inv. no. F102

In 1769, Riesener delivered a hugely expensive and highly acclaimed roll-top desk to Louis XV. Called the bureau du Roi (King’s Desk) thereafter, it was signed by Riesener and kick-started his career as a royal supplier. Five years later he was appointed official cabinetmaker to the new monarch, Louis XVI, and over the following ten years supplied more than 700 pieces of furniture to the royal households.

During that intervening period, however, Riesener established a healthy clientele of non-royal patrons who bought directly from his workshops in the Arsenal. One of these was the comte d’Orsay, who commissioned a desk from Riesener which was in direct imitation of the King’s Desk. It is the only example known of another roll-top desk matching the King’s Desk in size and scale, and it is likely that the young comte would have seen the King’s Desk at some stage and ordered a copy. As on the royal version, Riesener has signed Orsay’s desk, but here he has done so on a trompe l’oeil piece of paper made in marquetry.

This also gives us a clue about when he made it: engraved with the signature is the date, 20 February 1769. It is not clear what this date refers to exactly but it is probably the date of commission; the desk would have taken at least a year to complete, and Orsay’s aristocratic credentials are celebrated in the marquetry — as he was not created a comte until 1770, it appears that Riesener was still working on the desk at that time. For various technical reasons, the King’s Desk appears to have been the prototype.

It may appear unusual that Orsay was able to get such a close copy of the King’s Desk, but he was a very wealthy man and no doubt paid handsomely for it. Riesener has made some alterations to the decoration, particularly the gilt-bronze mounts which are less lavish than those on Louis XV’s model.

For example, there are no candle sconces at either side, and the double-faced clock with its gilt-bronze decoration has been omitted; the enormous gilt-bronze plaque on the King’s Desk has been replaced on this version with a marquetry panel depicting a woman holding her finger up to her mouth in a gesture denoting silence, or secrecy, a very appropriate allegory for a desk which may hold secret correspondence, and which demands quiet while its owner works at it.

Other beautifully-figured motifs include marquetry representing geometry and astronomy, the fruits of the earth and sea, and various military representations — all of which are found on the King’s Desk — and, in marquetry-framed roundels, Orsay’s initials: ORS.

The patron has been identified because of these initials, although for a long while it was thought that they referred to Stanisław I Leszczyński (1677–1766), former king of Poland and father to Louis XV’s wife, Marie Leszczyńska (1703–1768).

Orsay had inherited a sizeable fortune and when he came of age in 1766, he seems to have embarked on a life of conspicuous expenditure and art collecting.

He bought a house in the rue de Varenne in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, an old aristocratic neighbourhood of Paris, and set about redecorating it and furnishing it in the latest neoclassical style. He involved the most fashionable architects and designers, including Jean-François-Thérèse Chalgrin (1739–1811), the chairmaker Louis Delanois (1731–1792) and the cabinetmaker Jean-François Leleu, as well as commissioning Riesener to make this desk.

He was also a keen collector of paintings and sculpture, at the forefront of the renewing interest in classicism, and spent three years travelling in Rome and Italy, sending hundreds of cases of art objects back for his new house.

The desk was kept in his bedroom, the most important room in the house. Later, in 1787, alarmed by the mutterings of revolution around him he fled Paris for Germany and the home of his second wife, Marie-Anne, daughter of the prince of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg.

He let his house, fully furnished, to the English collector William Beckford who was later to acquire the desk after it had been seized by the Revolutionary government, confiscated as a work of art, and sold to raise money for the cause.

The desk has always been lauded for its magnificence and owned by great art collectors. It is not difficult to see why, with its superb marquetry, imposing gilt bronze and sophisticated interior, complete with drawers, shelves, inkwells and a hidden well with secret drawers under the writing surface to keep confidential correspondence.

The most idiosyncratic element, however, is a letter made in marquetry on the top of the desk, which is written in grammatically incorrect German. Could this be an indication of Riesener’s own literacy, and a highly personal memorial of the man himself?

For more information: Jacobsen, H. et al., Jean-Henri Riesener. Cabinetmaker to Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Furniture in the Wallace Collection, Royal Collection and Waddesdon Manor, London, 2020, no. 2.

The gilt-bronze mounts on these models have been rendered as far as practical for the Sketchfab platform.